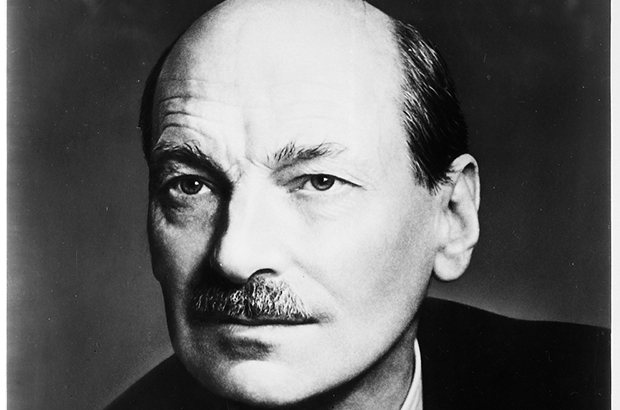

(Clement Attlee, Prime Minister 1945-51)

Following the war and the Labour Party’s landslide victory in 1945 over ten powerful industries were nationalised in Britain. Clement Attlee’s Party was seen as the country’s best hope for a revival from the war, ending war austerity and an avoidance of the depression of the interwar years. This meant a change of leadership. In this essay I will argue that so many industries were nationalised in Britain in the years immediately following WWII for three main reasons; the financial legacy of the war in the form of an ominous British balance of payments deficit, the war illuminating industries which full free-market capitalism didn’t work for and which central planning did, and the ideology of the Labour Party which saw government intervention as the only way to save these industries. These three factors, whilst not exhaustive, explain the reasoning behind public ownership in the period between 1945 and 1951.

Immediately following WWII there was one major topic at the forefront of the political and economic debate: how best to deal with looming balance of payments deficit. Owen in From Empire to Europe (1999) argues that one of Britain’s most pressing economic problems was the financial legacy of the war and it certainly seemed to be. Funding of the British war effort had been funded through borrowing money, the sales of many profitable overseas investments, and aid from the US in the form of the Lend-Lease program which supplied many Allied nations with essential material. The outcome was that Britain had “an alarming gap between foreign exchange outgoings and income from exports”. The aims of nationalisation from the Attlee government at this time were, therefore, to meet export targets, overcome the dollar shortage and boost exports. The decision to increase industrial ownership clearly stemmed from the need to meet these targets. Millward and Singleton (1995) argue that the large industrial firms in the United States, who showed high productivity in the absence of excessive competition on a domestic level, showed that the giant enterprise (of the type nationalisation of an industry through the merging of many small firms would entail) was more efficient and exploitative of economies of scale. Nationalisation was indeed believed to achieve this in the years immediately following the second World War and the Labour governments plans were shown to work, Britain’s economy was mostly back in order by the time they left office in 1951. By increasing efficiency and eliminating excessive profits from “key sectors of the economy” the Attlee government was able to reduce prices and costs and boost the economy, allowing the balance of payments deficit problem to be tackled. It appears clear, on the basis of this evidence, that the financial legacy of the war was an important factor in why so many industries were nationalised in Britain in the years following WWII.

The wars influence on the subsequent nationalisations was larger than financial. The war and interwar periods had shown that certain industries were unsuitable for free-market capitalism, ensuring their success required at least some government intervention, and that central planning could work. The Coal industry emerged from the war with a poor bag of assets (Owen), coal had suffered badly in the interwar period and was in serious decline. It was certainly in need of new investment and modernisation that the industry itself couldn’t sufficiently supply. Not only did the industry have financial problems but it had shown that it couldn’t handle its industrial relations problems between the unions and employers throughout the war. The nationalisation of coal in 1947 was, therefore, also seen as a way of resolving deep labour problems of the industry. Furthermore, there were three more industries amongst the many that were taken over in the years following the second World War: gas, electricity and the railways. These had been subject to regulation from the government before the war, Owen (1999) states that the arrangements between the government and industry hadn’t worked well and public ownership could be defended as a more effective means of ensuring that these natural monopolies were “managed effectively in the public interest”. The war and cooperation problems had shown that these industries weren’t capable or suitable to be open to free-market capitalism.

Moreover, Steel was seen as “important as a strategic commodity underlined in the fuel crisis of 46-47 and the balance of payments problems” and, of course, in the war effort. The nationalisation bill was first considered in 1947, but a compromise was made leading to increased government intervention but a delay of full nationalisation until 1949. The “advantages of cooperation between industry and government had been reinforced by war” here, Owen goes onto to state that the “Labour party’s position, and that of the principal steel trade union, was the industry was to be brought under public ownership”. It had been shown by war that central planning had worked and that cooperation and tariffs between government and industry worked well. Britain had won the war with an essentially state controlled economy, meaning that there was broad political consensus for government intervention in the economy. On the basis of this evidence it is clear that consensus for change into increased public ownership, which was due to the war showing the strengths and weaknesses of industry and government intervention, is a reason why so many industries were nationalised in Britain in the years immediately following WWII.

The post-war Labour party was ambitious, Attlee and some his closest colleagues had the party ideology close to heart when making decisions. They favoured a mixed economy in which the role the government would be powerful but not overwhelming. Whilst it can be argued that other factors such as restructuring and rationalisation are an explanation for nationalisation, it is clear that the Labour party ideology of eliminating excess profits, income redistribution and an increased role of the state were a major factor in why so many industries were nationalised in the years immediately following WWII. The “Labour party wanted the commanding heights of the economy in state control”, in other words, they wanted public ownership of steel, coal, electric and transport. Owen reports that although the Labour governments victory post WWII didn't mark the conversion of Britain to socialism, it was won on the manifesto of social reform and an extension of government control of the economy. The manifesto clearly lays out plans for public ownership of fuel, power, transport and iron and steel industries, stating that the steel industry as a “private monopoly has maintained high prices and kept inefficient high-cost plants in existence. Only if public ownership replaces private monopoly can the industry become efficient.” They believed that unification without public ownership would be bad for the rest of industry and for the general public, they wanted to reform the uneconomic areas of distribution. There was an inherent belief in the Labour party that these industries were in great need of government intervention if they were to best serve Britain, and that the market wasn’t ‘up to the job’. Whether it worked or not, with an overwhelming majority of votes, “the party could not be denied”. Furthermore, Steel was seen as the most ideological take over but it was “because of the complexity of steel nationalisation that the government excluded it from the first wave of nationalisation measures which covered coal, gas, electric and railway.” The Labour party ideology is, therefore, clearly a major factor in why so many industries were nationalised in their leadership of Britain in 1945-51.

To conclude, these three main factors best explain why so many industries were nationalised in the years immediately following WWII. The ‘financial legacy’ of the war put great pressure on the new government for industry reform, whilst the industries that showed their weaknesses were an obvious target to tackle. The Labour Party’s basic socialist ideology being at the heart of major decision making meant that government intervention in important industries was seen as the best way to deal with these economic pressures. An interesting continuation of this study would be to assess the success of nationalisation in these industries, and to make a comparison between Attlee’s government and economic reasoning for subsequent privatisations by the Conservative government that regained office in 1951.

Bibliography

Geoffrey Owen, “From Empire to Europe: The Decline and Revival of British Industry Since the Second World War” (Harper Collins 1999)

Robert Millward and John Singleton, “The Political Economy of Nationalisation in Britain, 1920–1950” (Cambridge University Press 1995)

Robert Crowcroft, “Attlee’s Britain 1945-1951, introduction to Attlee’s Britain” (National Archives)

Alec Cairncross, “Years of Recovery: British Economic Policy 1945-51” (Routledge 2005)

Leslie Hannah, “The Cambridge Economic History of Modern Britain” (Cambridge University Press 2004)

Peter Cirenza, LSE Lecture, Nationalisation 2014

No comments:

Post a Comment